|

Bob Post was killed. There was nothing special about his death except that he happened to be a newspaperman and the first one to be killed on an air mission, flying, of course, in total violation of the Geneva conventions. Harrison Salisbury, A Journey for Our Times

|

Note: Salisbury is almost certainly referring to the rule barring non-combatants from participating in combat. However, he may also have been referring to the weapons training that the Writing 69th received.

|

More than three dozen war correspondents for American news outlets died on the job during World War II. They came from every imaginable source, even The New Yorker, Reader's Digest, and Popular Science. The Associated Press and the United Press each lost five correspondents. The New York Times lost three.

|

The most famous was Ernie Pyle of Scripps-Howard. Pyle had worn himself out covering the war in Europe, but was convinced that he owed it to his country to return to war coverage. He was killed by Japanese machine-gun fire on the island of Ie Shima.

|

Frederick Faust, who wrote the original Dr. Kildare novels under the pen name "Max Brand," died with an infantry unit in Italy while covering the war for Harper's. Faust was the author of over two hundred books of popular fiction, but poetry was his love, and when he was killed by a mortar blast he was said to be carrying an unfinished epic poem.

|

David Lardner, son of the sports writer and humorist Ring Lardner, was a correspondent for the New Yorker. He died when his jeep hit a mine in Germany. Lardner's traveling companion had suggested a shortcut that went through a recently cleared mine field. Traveling in darkness, the jeep driver brushed against a pile of mines. Lardner and the driver were killed in the resulting explosion. The traveling companion survived.

|

New York Times correspondent Harold Denny is listed in some accounts as having died as a war correspondent, though he died in Des Moines of a heart attack. Denny had spent time interned in Italy and had been wounded in the same attack that killed fellow correspondent John Frankish. For those reasons he is sometimes included even though he didn't die in action. A heart attack also claimed Reader's Digest correspondent Frederick Painton (who was in Guam at the time).

|

Of the correspondents to die, Leah Burdette of the New York newspaper PM was the only woman. Burdette died in 1942 when her car was ambushed by bandits in Iran.

|

Webb Miller of the United Press was killed when he fell from a train during a London blackout. German press reports of the time speculated that he had been killed by the British secret service, perhaps, they said, in retaliation for his sympathetic portrayals of the Germans.

|

Leyte was the most deadly destination for World War II correspondents. One terrifying explosion in Leyte claimed the lives of three correspondents: Asahel Bush of the Associated Press, Stanley Gunn of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and John Terry of the Chicago Daily News. Weeks later Acme Pictures cameraman Frank Prist was killed by a sniper in Leyte.

|

Bob Post wasn't the only civilian correspondent to die on a bombing mission. Two correspondents died on RAF missions: Ralph Barnes of the New York Herald Tribune and Jack Singer of the International News Service. John Andrew (UP), John Cashman (INS), Raymond Clapper (Scripps-Howard), Harold Kulick (Popular Science), and William Schenkel (Newsweek) all died in U.S. bomber crashes. Two others, Frank Cuhel (Mutual Broadcasting System) and Ben Robertson (New York Herald Tribune), died in the 1943 crash of a Clipper plane on a commercial flight from New York to Lisbon.

|

Associated Press reporter Joseph Morton was executed along with the group of commandos he accompanied into Yugoslavia. His captors were punished as part of the Nuremberg trials.

|

Robert Bellaire of Collier's survived internment by the Japanese only to die in a jeep crash just weeks after the Japanese had surrendered. He was the last of the American correspondents to die.

|

Bob Post's death has been reduced to a footnote in the history of journalism. When the plane carrying Commerce Secretary Ron Brown crashed in Bosnia in 1996, another New York Times correspondent died: Nathaniel Nash, the Frankfurt bureau chief. A spokesman for the New York Times noted:

|

Not since the early stages of World War II have we lost anyone on assignment. Joseph Lelyveld, New York Times (as quoted in the Boston Globe, April 4, 1996)

|

Of course, that was Bob Post.

|

In the short term, Post's death made editors rethink their decision to send correspondents into danger, but in the long run most correspondents just went back to their dangerous occupation. They continued to fly with the bombers on occasion, and they accompanied troops on the front lines.

|

Less than five months after the Wilhelmshaven raid, the New York Times allowed Herbert Matthews to participate in a bombing mission. Matthews accompanied six other war correspondents on an Allied air raid on Rome. The others were: Raymond Clapper of Scripps-Howard, Richard Tregaskis of INS, Joseph Morton of the Associated Press, Richard McMillan of the United Press, J.H. Nicholson of Reuters, and Tom Treanor of the Los Angeles Times. Although all returned safely that day, three (Clapper, Morton, and Treanor) would die later in the war on assignment.

|

Like many other war correspondents, the members of the Writing 69th were highly motivated individuals who were willing to put themselves at risk to get a good story. Did they think these stories were important enough to risk their lives? Of course. Did they ever have their doubts? Certainly:

|

Was it really necessary for me to volunteer for a mission that could easily cost me my life simply to get a story for the newspaper or to appear more legitimate in the eyes of the crewman I was covering on a daily basis? Andy Rooney, My War

|

But they were young, and thought themselves indestructible:

|

I just had the feeling that I'd make it back safely. You know how that is sometimes? Of course, I suppose a lot of people had that same feeling who didn't make it.

Leon Johnson as quoted by Andy Rooney in "My War"

|

Note: Colonel Leon Johnson, one of the most famous members of the 44th Bomb Group, was awarded the Medal of Honor for the low-level raids on the oil fields of Ploesti, Romania on August 1, 1943.

|

Bob Post was driven, but he didn't expect to make it back.

|

Bob Post's death further diminished the status of the B-24, which was already overshadowed by the B-17 as far as the Allied press corps was concerned.

|

Newspapers often neglected to mention the fact that the B-24s went out at all and raid stories read with tiresome regularity for the Lib man "Flying Fortresses Attack Sub Pens in Daylight"-no mention of the Liberators, which did a good job, took a beating, and returned home with little but official credit for the raid. Andy Rooney, Air Gunner

|

Today, B-24 veterans continue to lament what they see as the lack of public acclaim for their bomber. A typical example is what happened following the death of movie actor Jimmy Stewart. Stewart flew combat missions as a B-24 pilot during the war, but some newspaper writers assumed that since he was a bomber pilot, then he must have flown a B-17. This factual inaccuracy deeply disappointed many B-24 veterans who are rightly proud of their airplane. Oddly enough, the German wartime press thought that the B-24 Liberator had been the target of overly enthusiastic praise. The day after Post's death an Oldenburg, Germany newspaper published a photograph of the wreckage of Lt. McPhillamey's B-24 and reported the following:

|

We have not yet forgotten the pompous and bragging announcements of the enemy press and British radio that celebrated the U.S.'s "Liberator bomber" upon its arrival in England. Oldenburg Nachrichten, February 27, 1943

|

The B-24 Liberator and the B-17 Flying Fortress had names that were packed with symbolic meaning. Both terms had been popularized by the military and were promoted heavily in the press. The Writing 69th was another name that was created for promotional purposes, and it served to tie together eight men who had been covering the air war. However when Bob Post was lost, his death marked the end of "The Writing 69th." Of course, the journalists continued their work, they just stopped using the name. Ironically, the Writing 69th proved something to the public that the 8th Air Force would just have soon not have advertised, that is, the extreme risk faced by the airmen who participated in these missions. Bob Post knew that he was taking a one-in-ten gamble with his life. He even thought that he would be the one to die. And he was right.

|

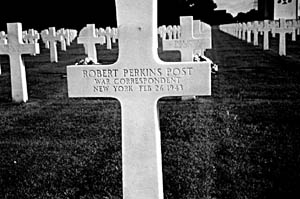

Bob Post's grave at Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium - Photograph courtesy of Will Lundy

|